By Art Rosengarten, Ph.D., January 21, 2000.

Like many of my generation, I still hold the Sixties with reverence for its underlying vision, its music and emotion, its call for change and possibility. Such things resounded through my youthful imagination like thunder through lightning.

In the Seventies I did graduate study in philosophy, religion, and psychology in San Francisco, and discovered the practice of psychotherapy to be the perfect professional calling. Compassionate and intuitive, creative and effective, intellectual and spontaneous, how better to align my spiritual and artistic passions with meaningful employment?

I was then first introduced to Tarot in a Graduate Weekend Seminar. Despite my innate cynicism for faddism and fakery, I was touched to the bone by the cards. All questions and answers of a personal nature seemed to coalesce under their spell. I spent the next three years during off hours from my clinical practicums making daily Tarot experiments until my world, such that it was, seemed more an outer confirmation of my cards, than the reverse. Words failed to describe the compelling synchronicities of this phase, and I remained largely in hiding like some protective keeper of great secrets.

Then came the Eighties. I wrote the first accredited doctoral dissertation on Tarot (which I compared with dream interpretation and projective storytelling) and demonstrated statistically the reliability and validity of the Tarot method. This was amazing, but I didn’t know how to estimate exactly how amazing? I asked my Committee Chair, a well-known expert in the field, how my findings would be met in the conventional academic world? He said my study would probably garner more interest if I had demonstrated Tarot’s lack of validity and reliability. Academic psychologists would chomp at the bit to scientifically dismiss Tarot as another medieval anachronism. Even the Parapsychologists (wolves in sheep’s clothing) would likely be uncomfortable (threatened) by a mantic method that couldn’t easily be controlled in their experimental trials. (Technically, Tarot readers are not psychics, but diviners). So much for my noble efforts.

I put the work on hold and focused instead on my clinical development in conventional psychology. Through internships and Fellowships I worked for years in private psychiatric hospitals, residential treatment centers, and eventually full-time private practice which I continue to this day. I took as much advanced training and personal analysis as I could, and received two professional licenses in California. But I was not done with Tarot. I continued teaching, reading professionally, and experimenting on the side. I knew the power of conventional psychotherapy, and indeed the beauty, yet to my mind it paled next to the potentials of an instrument like Tarot.

I put the work on hold and focused instead on my clinical development in conventional psychology. Through internships and Fellowships I worked for years in private psychiatric hospitals, residential treatment centers, and eventually full-time private practice which I continue to this day. I took as much advanced training and personal analysis as I could, and received two professional licenses in California. But I was not done with Tarot. I continued teaching, reading professionally, and experimenting on the side. I knew the power of conventional psychotherapy, and indeed the beauty, yet to my mind it paled next to the potentials of an instrument like Tarot.

I felt strongly that the real Tarot has been improperly lumped with gypsy folklore, raffish occultists, and New Age-ism and if it belonged anywhere given its Italian Renaissance roots, it would more likely find its natural home in the psychology of the individual, including Jungian, Humanistic, Dynamic, and even Existential psychologies. Other systems, particularly in this turbulent age of brief, cost-contained, issue-targeted modalities, might also benefit from Tarot’s rich, image-based, multi-level, non-linear language which seems to possess some uncanny knack for mirroring subjective experience. Nowhere does it say psychotherapy must remain dull.

Unfortunately, I could not find a single book that did poetic justice to the spectrums of psychological meaning and healing laden in Tarot. I decided if I couldn’t read it, I would have to write it myself. I prefer not to be alone. TAROT AND PSYCHOLOGY: SPECTRUMS OF POSSIBILITY has been a most satisfying culmination of this love affair.

Art Rosengarten

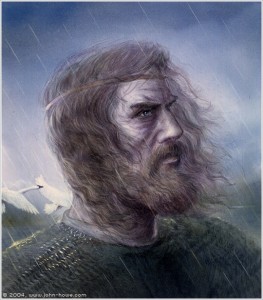

One day King Arthur is out hunting in the North, in Inglewood Forest, where he stalks a white hart until he wounds it with an arrow. Just as he goes to gather his kill, a monstrous fellow steps out of the woods. He calls himself, “Sir Gromer Somer Jour” and threatens Arthur instantly with death by his ax. Shaken and confused, Arthur responds that he is unarmed for battle, and Sir Gromer grants him a twelve-month span in which to answer a riddle or return for his death blow. King Arthur departs this encounter entirely crestfallen and confused about the intent of the riddle.

One day King Arthur is out hunting in the North, in Inglewood Forest, where he stalks a white hart until he wounds it with an arrow. Just as he goes to gather his kill, a monstrous fellow steps out of the woods. He calls himself, “Sir Gromer Somer Jour” and threatens Arthur instantly with death by his ax. Shaken and confused, Arthur responds that he is unarmed for battle, and Sir Gromer grants him a twelve-month span in which to answer a riddle or return for his death blow. King Arthur departs this encounter entirely crestfallen and confused about the intent of the riddle.